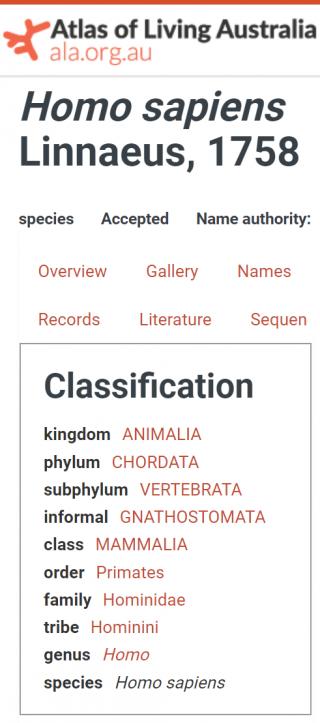

| Taxonomic names for biological entities have a rigorous scientific process for formulation, publication and application. They are the ‘handle’ by with all other information concerning the taxon (… family | genus | species | subspecies …) can be meaningfully communicated and aggregated.

Not only are they globally unique (within each kingdom of life), but they connote relationship between organisms via the names hierarchy ( see Figure 1). As systematists refine knowledge of their specialist group and gain a more complete understanding of relationships (via morphology and/or genetics) these names can change. In simple cases, a species ‘new to science’ is added to an existing genus, or an existing species is found to contain more than one entity and so is split into two species, of which one retains the same name. In more complex situations, one or more species are found to be more closely related to species in a different genus in the same family. Occasionally, this can happen to whole genera! In short, tracking scientific names, their currency, concept and relationships, is somewhat of a ‘wicked problem’, especially in one of the world’s megadiverse biodiversity hotspots. Scientific names also have a very particular link to specimens. There is always at least one specimen, usually vouchsafed in a scientific institution such a museum or herbarium, to which the author refers to in the original description of that name. This is known as the ‘Type specimen’ and holds the concept of what that name physically represents. Later scientists will need to refer to this specimen in order, for example, to satisfactorily determine that new material does not belong to that taxon concept and so may be considered a new species. As this Type specimen is housed in a single institution, either replicates of that specimen (if any were collected from the same organism as part of the same collecting event) are distributed to major institutions on other continents, or more recently, a high-resolution image is made available via the ‘net. In any case, it is the role of taxonomists and curators in collections institutions to ensure adequate information is provided to allow correct identification of new material AND to provide linkages to names as they accrete against a species. This allows interrogation of biodiversity knowledge bases with any previous name to find its currently-accepted name. |

|

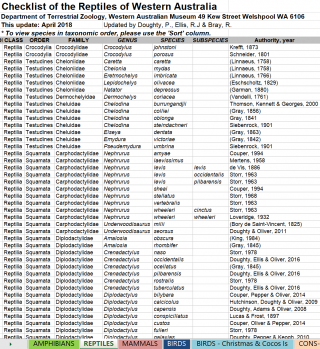

| In Western Australia, the two primary biodiversity collections are the Western Australian Herbarium and the Western Australian Museum. Until the early 1990’s both used their specimen collection as a method for publishing a census or checklist of the species occurring in WA. Since that time their methods for managing and communicating flora and fauna names have diverged. The WA Museum, with nine distinct biological collections, continues to produce +/- yearly checklists of current names uttered in their specimen collection. These are more recently available in a downloadable spreadsheet or PDF formats (see Figure 2). While this makes the names readily accessible for re-use by users external to the Museum, finding out what happened to previously-known names requires reference to one or more ‘what’s changed in this version’ documents or knowledge of the source literature.

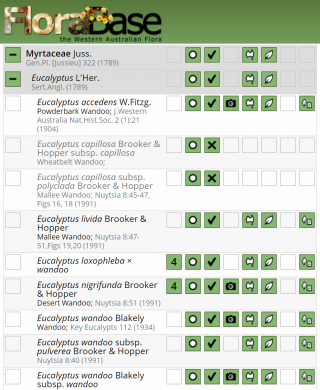

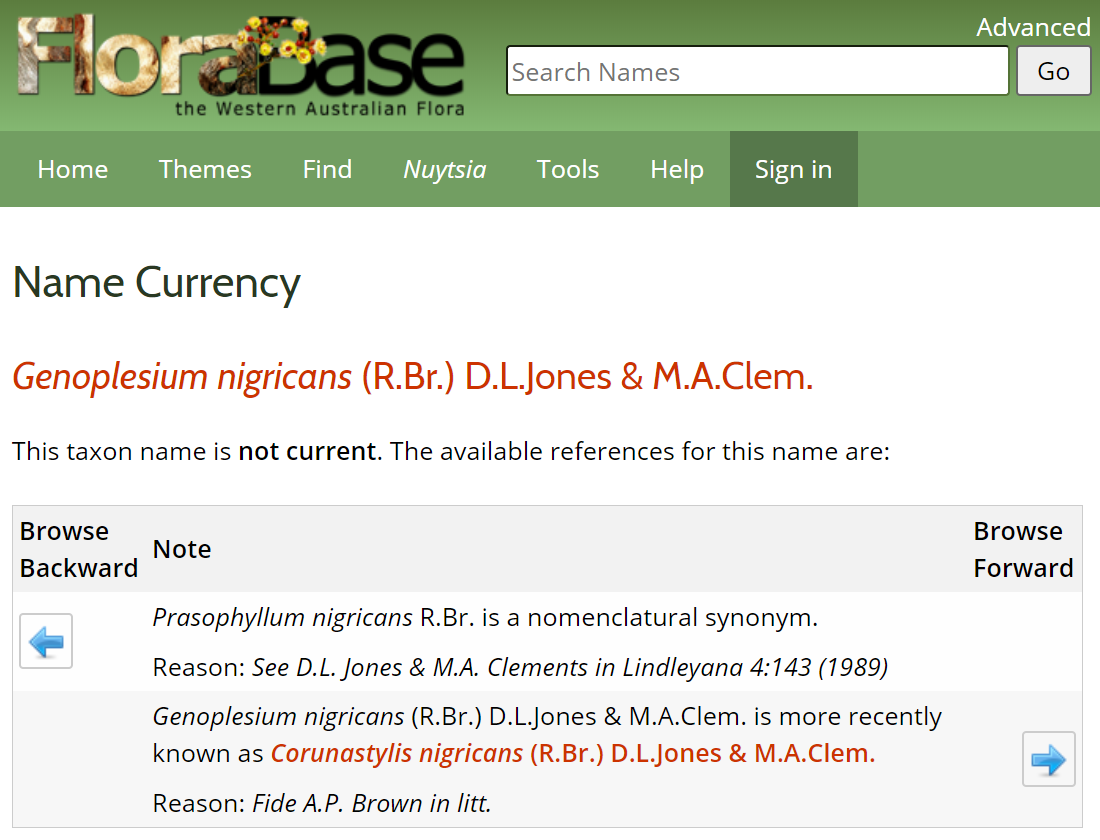

The WA Herbarium has published a printed Census of the State’s vascular flora a number of times over the last century, that include both current and previous names. Since 1990, the flora names have been managed in a database separate to the specimens, which enables specific names-related information (eg. synonymy, conservation status, imagery) to be discretely managed, and communicated via their web portal FloraBase – the Western Australian Flora (Figures 3, 4). Since 1993 the names and specimen data tables have been directly linked. In procedural terms, the WA Museum primarily relies on the curation of specimens and the updating of their specimen databases to supply the current names for each checklist. This likely requires some subsequent vetting of these lists by the responsible curators to ensure recent changes from literature are correctly applied. In contrast, the WA Herbarium primarily uses the scientific literature to capture relevant name changes for the State, adds them to the Census, which then makes the names available to apply to specimens and the consequent database updates. This method ensures a single point of names reference without further checking. |

|

| Since the advent of DBCA’s NatureMap (Figure 5) which provides a spatial view into most of the Department’s biodiversity datasets, subsets of the WA Museum names data have been semi-manually ingested into the Census, which has become the de facto ‘Census for the WA Biota’. Clearly, the provision of the core set of currently accepted names for the biota of WA underpins any streamlined delivery of authenticated biodiversity information.

FloraBase, which delivers real-time data from the Western Australian Herbarium’s census and specimen databases, along with conservation and naturalised status, distribution maps, images and taxon descriptions. It has been delivering this data for vascular and some cryptogamic groups for over 20 years and key to its success was, I believe, building the web portal to be closely tied to the maintained source datasets. Western Australian Herbarium and Museum scientists and curators also play a critical role in maintaining the Australian National Species Lists (Figure 6) for currently-accepted flora and fauna names, either by publishing new taxa in the scientific literature and/or reviewing taxonomic nomenclature and current concepts of species delimitation and distribution. The dwindling pool of taxonomic specialists continue to maintain the currency of knowledge about the biota but, while innovation in information technology can speed the accurate delivery of existing information, it cannot replace the scientific process for evaluating and recognising new species and taxon concepts. |

|

If you’d like to talk further about taxonomy, systematics or names management, contact me directly via email (alex.chapman@gaiaresources.com.au), or through Facebook, Twitter or LinkedIn.

Alex

Comments are closed.