When Jake and I went across to Melbourne for the FOSS4G conference in November, I took the opportunity to catch up with some of our Victorian clients. One in particular was the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) whom we work closely with on the Atlas of Environmental Health and mosquito monitoring. It was great to grab a coffee and catch up with a few of the staff there who I hadn’t met before except across video conferencing and e-mails. Also it was a nice way to mix up and end a week otherwise spent listening to presentations about spatial systems and products.

There’s no substitute for face-to-face time when you want to learn about your client’s business and state of mind. By meeting with the public health entomologist, epidemiologists and analytics officers in the Communicable Disease Prevention and Control team I was able to learn a lot about business context and challenges around data, systems and reporting, and also the relationship between communicable diseases and on-ground mosquito monitoring activities. Fortnightly reporting and access to solid, accurate data is critical to fortnightly reporting and managing risk across a range of infections and diseases. Somehow the emails we are so used to using and phone calls boil down to just what you need to know for an immediate task or issue. The context can easily be lost, or not fully translated compared to when you are physically present and seeing what your clients are dealing with.

This trip didn’t have a field excursion like the one we did back in 2017 (see link to that blog here), but just as interesting I was able to sit down with an analytics officer and see how DHHS are tapping into the Atlas and other systems to build up their reporting outputs through PowerBI. Part of our latest phase of work with these guys to build an Application Programming Interface (API) so that analytics packages could draw data from the Atlas and combine that with other Health systems data (e.g. health facilities and their capacity to deal with outbreaks).

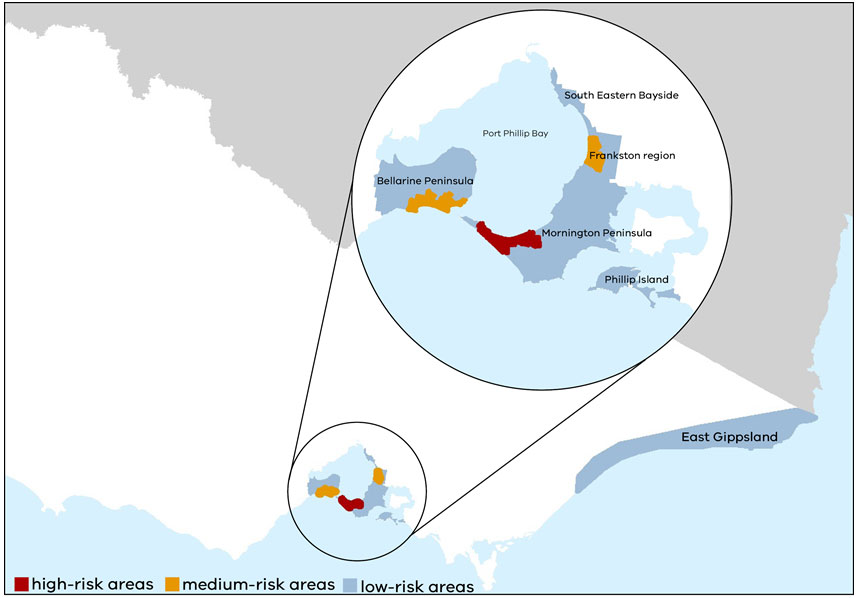

The fortnightly reports are part of critical presentations that senior officials in DHHS use to make strategic decisions for the health of Victorians and their facilities. Apart from keeping an eye out for Ross River Virus, health departments in Australia need to monitor for Murray Valley encephalitis virus, Barmah Forest virus and dengue virus. Lately, Buruli – known as the Bairnsdale ulcer in Victoria, and the Daintree ulcer in Queensland – has been making the news in Victoria (click here for the Victorian health alert). It is an infection caused by a flesh eating bacteria called Mycobacterium ulcerans that has been on the increase in parts of coastal Victoria, and the primary theory is that the virus is transmitted by mosquitoes.

Map of Buruli ulcer risk in Victoria (source: Health Victoria alert 18002).

Not all mosquito species carry diseases of course – in most cases they are just an itchy nuisance; however, it is through monitoring, trapping and laboratory species identification that health officials can spot an impending risk of particular species breeding who may carry these viruses. Through the Atlas of Environmental Health we help DHHS to use visualise the location, clustering and temporal patterns of data regularly collected in the field.

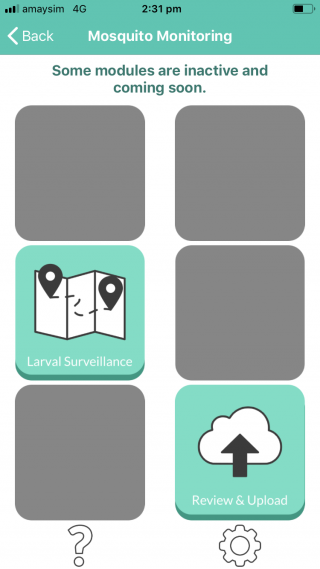

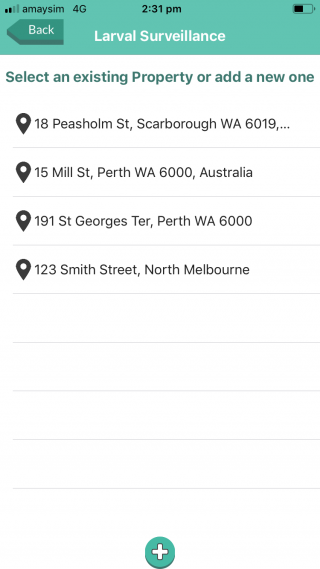

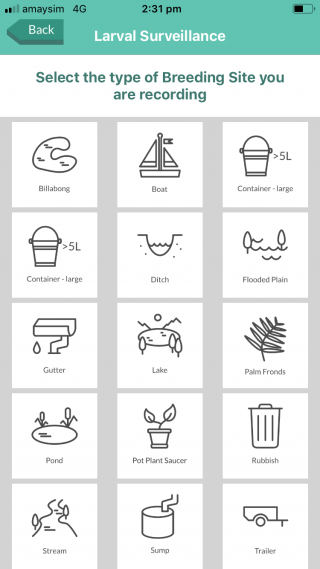

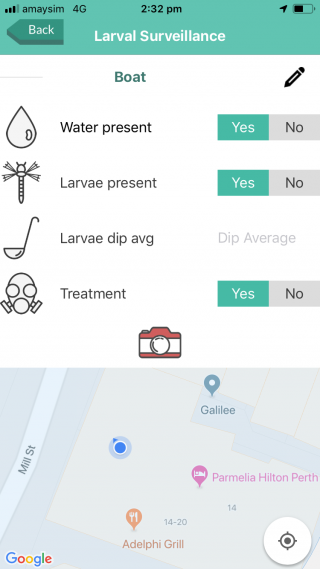

The biggest component of our recent phase of work though has been a new Ground Surveillance Module (GSM) mobile application. The GSM module – currently being tested – focuses on rapidly inspecting and collecting data on breeding sites at a property level. The app has features and a workflow designed for a minimal click experience – like responsive screen progression, GPS based reverse geocoding (a fancy term for pre-populating a property address), and geotagged photographs.

Through simple design the app is getting a neat refresh, which includes reverse geocoding

This GSM app will in future incorporate the adult trapping, larval dipping and public complaint functions currently used in our mosquito monitoring app – bringing the existing functionality into a more flexible and easier to maintain application framework. With mobile technology maturing we wanted to ensure that DHHS was able to take advantage of the new features that are on offer. The most significant of these is parallel platform development for iOS and Android, which results in efficiency savings in development and maintenance.

With the GSM app, local government Environmental Health Officers (EHOs) will be able to capture locations of potential breeding sites through property inspections along with information about whether mosquito larvae are present and whether a treatment was applied. In some cases this would be as basic as removing the water source from a bucket or pot, while in others the EHO may be able to apply a treatment or need to return at a later date. The rapid entry of data is all about increasing capacity of the EHOs to cover more ground, and to generate a more accurate and timely picture of what is happening across their local area. Larvae breeding in a backyard pond or container typically mature in about 2-3 weeks, after which time a different and trickier treatment type is required, so the app and increased coverage is important for DHHS to manage threats of a disease outbreak. As with risks in most disciplines, if you can identify it early you have more choices about mitigation before it turns into an issue.

Simple designs using icons and graphics to streamline data capture is very important for efficient use of the app

If you think about what the EHOs are doing as they visit properties, the rapid data entry gives them time to be more public facing and to engage with people in a useful conversation about preventative measures. They can take the time to show residents and business owners where mosquito breeding can happen, and simple approaches to prevent standing water from turning into a problem. Overturning empty buckets and pots, and keeping pool and pond water circulating over winter for instance, can go a long way to avoid both the unpleasant barbecue experience and serious health problems.

So through this latest phase of work we have added a new app for field data collection and have built an API for connecting the Atlas of Environmental Health to other analytics packages. I think 2019 is going to be an interesting time in this space as we look to solidify these tools and ramp up capabilities in data collection and risk reporting. If you’d like to know more about this topic, strike up a conversation with us on our Facebook, Twitter or LinkedIn accounts – or drop us a line on (08) 9227 7309 or email me on chris.roach@gaiaresources.com.au.

Chris

Comments are closed.