On the 11th November 1998 I made a presentation to the herbarium staff at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew on the day ‘FloraBase – the Western Australian Flora‘ was launched onto the internet. Three years in development, the site was an access point into the rich biodiversity specimen data contained within the vaults of the Western Australian Herbarium. As the appointed Australian Botanical Liaison Officer (ABLO) that year, I was the eyes and ears of the Australian botanical community in one of the most significant herbaria on the planet, containing much of the critical Australian type (original) specimen material so crucial to determining the correct application of plant names in Australia.

To present FloraBase to that audience was a special moment – one of the first herbaria to have their entire collection online, and in one of the world’s 35 biodiversity hotspots. It had taken a lot of hard work – some of that is described in the Landscope article published this week to recognise the 20-year milestone for the FloraBase site, co-authored with herbarium colleagues John Huisman and Ben Richardson. Crucial to this work was the:

- creation of a specimen database to house the State’s herbarium collection documenting, via specimens and label data, the plant biodiversity and distribution across the State. Started by Curator John Green in 1985, I took over the management of WAHERB in 1989; the collection was fully databased by 1994 and maintained subsequently;

- development of the State’s vascular plant census, published in print in 1985, but converted to a proper database format by Nicholas Lander, and then implemented in its current form (WACENSUS) by Paul Gioia and I from 1990 onwards;

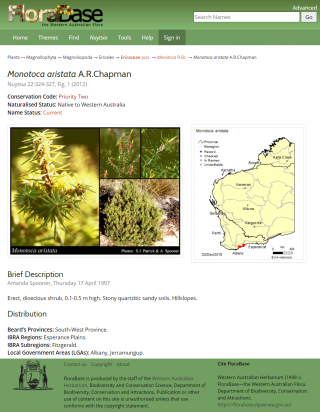

- Descriptive Catalogue project, developed between 1993 and 2000 when it was published in hard copy and incorporated into FloraBase to provide simple identification and descriptions across the whole flora – some 11,922 taxa occurring in the State at that time — it was maintained and updated for a further eight years;

- development of curated images to illustrate the habitat, habit and diagnostic features of each taxon — all achieved through a large citizen science effort primarily from the WA Wildflower Society volunteers; and

- automated and regular calculation of simple distribution maps for each taxon.

An example taxon profile page illustrating the aggregated elements (names, images, specimen map and a description). FloraBase continues to be heavily used since the launch in 1998 (and relaunch in 2003)

By positioning the specimen, names and image databases right within the curatorial purview of the WA Herbarium, and providing useful tools for the curators and scientists, the systems were quickly adopted. Many curatorial processes were realigned or adjusted to incorporate the databasing procedures, and once the World Wide Web came into existence in 1994, the development of FloraBase on top of these existing systems was a compelling enhancement.

After my stint as ABLO and the launch of FloraBase and the early AVH versions, I became further involved in the development of international data standards as the Oceania Secretary of Biodiversity Information Standards-TDWG in 2002 and attended a number of international meetings to develop the Access to Biological Collection Data – ABCD – a global schema to allow all biological collections to be shared and aggregated. These two data standards projects were crucial to the development of the Global Biodiversity Information Facility – GBIF and shortly thereafter, the Atlas of Living Australia – ALA.

Back in WA, FloraBase 2.0 was launched in 2003, with major functional improvements and the State’s systematic botanical journal Nuytsia, of which I had been the editor for a number of years, also became part of FloraBase.

I had seen work that Gaia Resources had been involved with, such as building an ImageBank solution for the WA Herbarium to manage over 50,000 taxon images and their relationship to name and identification changes. They also implemented the first data engine for the ALA to manage and integrate species data from a multitude of contributing source, and to initiate management of their citizen science interactions. When I moved on from the WA Herbarium, joining the Gaia Resources team was the best next step to help guide their work on the State’s biodiversity informatics infrastructures. Two relevant early projects were the:

- construction of a single home for the WA Museum‘s many disparate specimen collections databases; and

- initial implementation of a unified collections management system for the CSIRO’s National Research Collections.

Flip forward to 2018 – and all the systems mentioned (apart from the two above), though innovative in their time, are now ageing and in need of replacement. At the same time, the world has moved into the era of big data, where smart tools can work over large-scale aggregated data sets to allow mere humans to deduce appropriate actions. While the fundamental curated datasets are irreplaceable, new technologies must be put in place to enable their continued longevity. Data standards must be utilised to help aggregate data to a State level to enable agencies such as the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA) or the Department of Water and Environmental Regulation (DWER) to get on with its work on conserving and managing the State’s biota. Initiatives such as the WA Biodiversity Science Institute – WABSI are heavily involved in supporting this sort of work.

Recent Gaia Resources work on creating a flexible data repository for State agencies’ biodiversity data (see last week’s blog about our work with the DBCA on Biosys) show the way forward for flexibly storing ‘big’ biodiversity data.

A new generation of data management and systems integration is required today to enable effective dissemination of biodiversity data across multiple agencies. Decision-makers require the best-available information to hand in order to make good decisions for conserving the environment. New methods enabling such critical analysis must be envisioned while ensuring the critical core information systems continue to be upgraded and maintained into the future. One recent excellent example of such new tools is the Threatened Species Recovery Hub’s Australian Threatened Bird Species Index.

As was alluded to last week, we’ve been brainstorming ways in which that can happen here at Gaia Resources – which I’ll blog about in the new year – and we stand ready to help achieve these crucial tasks. As always, we can be contacted directly via email (alex.chapman@gaiaresources.com.au), or through Facebook, Twitter or LinkedIn.

Alex

Nice work!